Building Culture

Architectural features/main typologies/functional organization of the buildings

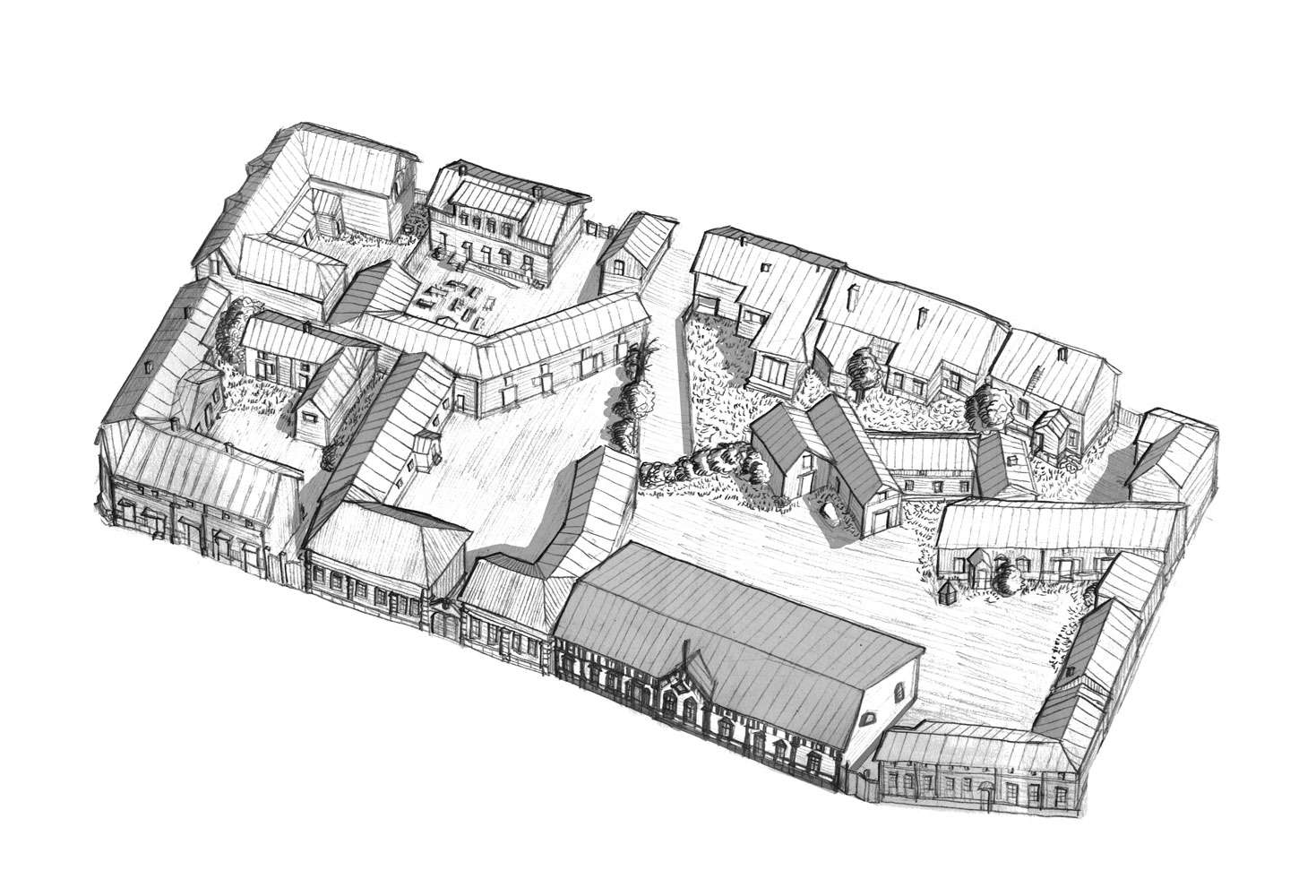

Traditional dwellings in Old Rauma came to be as a result of the addition of small nuclei grouped within the same building, usually linear volumes or simple L- or T- shapes, the highest built on two levels with a basement below, under a single roof. Entrances can be found in different spots: along the outer edge directly giving onto the street, inside the courtyard, or in the chamfered corners of the block (Raitio, Tammi, 2018). Usually, the middle floor is the only inhabited space, while the other two (basement and attic) remain empty and are used to ventilate the entire building or for secondary domestic activities. Building height varies substantially and is especially dependent on the typology of foundation and plinths. In some cases the buildings have no basement so that the foundations are simple individual stone elements, which means that the dwelling rests almost directly on the ground. However, in other cases, especially in areas where the ground is uneven, the dwellings make full use of very high plinths.

The architectural composition of these houses is usually made up of three horizontal volumes: the stone plinth or base of the building, which corresponds to the basement; the main body of the house or external timber-clad walls, with windows, doors, and the entire system of cornices and decorations of the buildings; and the roof or attic (Mattila, 2014), sometimes complemented with storm windows for lighting, with gable or hip roofs usually waterproofed with painted corrugated iron. Secondary buildings follow the same composition criteria, albeit simpler and undecorated.

The traditional lifestyle was quite modest: the nucleus of the dwelling was usually made up of one or two large rooms where all activities were carried out, both during the day and night. Each room tended to have its own stove, a key element in dwellings, where they were not only the main source of heat but were also used for cooking (Nurmi-Nielsen, Lybeck, 1984).

Each housing unit was usually accessed through an entrance area which connected the different dwellings. The buildings had no running water or sanitary facilities indoors, so water was usually obtained from wells, which were generally public.

A final characteristic element is that of names: almost every building displays its own name, written in Gothic script on an oval plate on one of the outer walls. The names go back centuries to when the houses were named after the owners.

Features of building techniques

Traditional buildings, the most widespread building typology in Old Rauma, are almost always simple pine buildings. However, it should be noted that some masonry buildings date back to the 19th century, some new concrete buildings to the 20th century, and that the church of the Holy Cross and the original Town Hall were built in masonry and brick.

The foundations of the dwellings are usually large stone ashlar walls 1–1.5 m down in the ground. Furthermore, these walls also support the wooden beam under the upper logs that make up the outer building walls (Salo, Sundelin, 2015).

The traditional floor and roofs are wooden, usually consisting of a grid of main beams around the perimeter and half-log beams or crisscross boards, on which insulation (moss or other natural fibres and gravel) rests. The bare wooden floorboards are sometimes covered in linoleum, a material frequently used in the 20th century (Caruso, 2019).

The walls are built by piling wooden logs assembled at the corner. The exterior walls are separated from the ground by the main beam running along the stone walls of the basement. Strata of fibres are placed between the different rows of logs in order to level and aid insulation. The interior walls are built in the same way, although they rest on a main beam supported at the ends by brick cubes or piled bricks. It is also worth noting the existence of brick walls built around the stoves. Walls are usually clad on the outside with timber boards and decorative mouldings, while the interiors are covered with ornamental wallpaper (Raitio, Tammi, 2018).

Traditional roofs are truss roofs, made up of wooden boards, often covered with corrugated iron, already used at the end of the 19th century. Doors and windows are traditionally made of wood, with shapes and styles which have changed over time and fashion. Windows are generally double glazed to prevent heat loss while letting in daylight.