Models

Explore interactive 3D models

Located in central and southern Albania, Berat and Gjirokastra historic centres were added to the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2005, thanks to the valuable presence of several remarkable examples of Ottoman-styled houses and for the integrity of their vernacular urban landscape. Born for defensive purposes, the architectural typology that characterizes these cities is that of the tower house (Kulla). The lower floors of the buildings used stone as the main material of the walls, reinforced by wooden elements, the upper floors are made of mixed structures with a wooden frame. In Gjirokaster, the roofs are in stone slabs, and in Berat, they are in roof tiles. The activities carried out in Gjirokastra are aimed to analyze the local building culture through the use of the instruments of survey and digital representation, and with the collaboration of students and local experts. The investigation activities were carried out adopting an interdisciplinary approach and using both traditional and advanced data gathering techniques.

Zekate House, Albania

Learn more about Gjirokastra & Berat, Albania

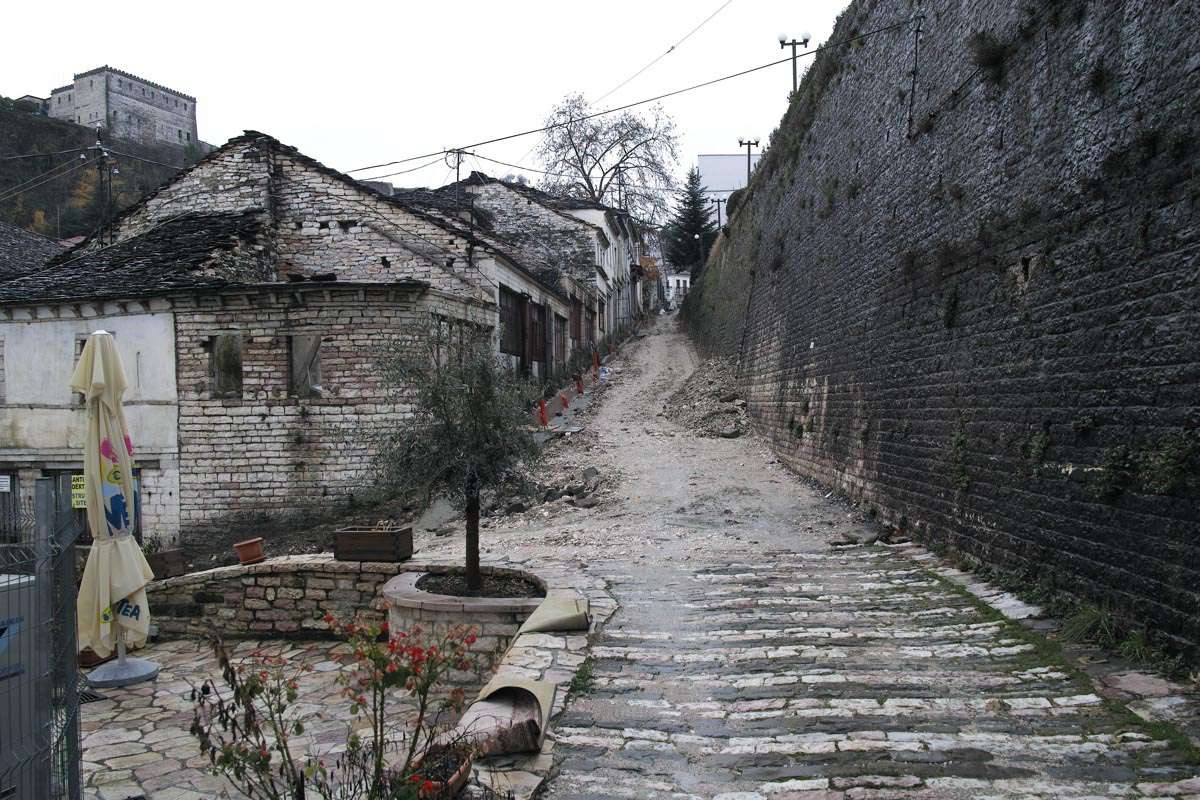

The historic centres of Berat and Gjirokastra, located in central and southern Albania, were added to the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2005, thanks to the valuable presence of several remarkable examples of Ottoman-styled houses, and to the integrity of their vernacular urban landscape. Gjirokastra was founded on the slopes of the Drino valley, in a strategic position that satisfied the strong need for defence, but imposed some important limitations to the builders. The main structure of Gjirokastra consists of two ridges standing out from the massif: the Rruga Pazari i Vjeter Pllake runs on the first ridge (in the South), dominated by the Castle, and the Rruga Alqi Kondi runs on the second ridge further north. Towards the mountain, at the junction point of the two ridges, just where the valley that separates them is not so wide, we find the Bazaar district, the true nodal point of old Gjirokastra, with its characteristic crossroads. From the bazaar, the Rruga Ismail Kadare follows the slope of the ground and becomes part of a sort of chessboard located on the wide slope overlooking the valley and lying to the limit of the old centre, a ravine at which the extension towards the valley of the Bulevardi 18 Shtatori arrives: an important road, perpendicular to the river, marked the expansion of the modern city on the valley.

Berat is located approximately 120 km south of Tirana and has stood for more than 2,400 years. The city is situated in an overview location between the mountains Tomorri and Shpiragu. It arises on sloping and rocky ground and its urban layout is structured on two hills facing each other, and separated by the river Osum. The citadel is located on the northern hill on the Osum River. In front of the citadel there is a smaller fortification (Gorica Castle), which is now in ruins. This urban morphology, consisting of two fortified sites on two hills facing each other, has been effective for the defense of the valley around the river, and it was the base for all the following developments of the city.

Gjirokastra was a meeting place for Greek, Roman, Byzantine and Ottoman cultures, stretching South-East/North-West and enhancing its defensive potential thanks to the position of control between the Ionian Sea and the Balkans. Until the end of the 19th century, the perimeter of the city centre was drawn by the lines leading to the Castle, corresponding to the ridges perpendicular to the Mali i Gjerë massif (around 1800 metres above sea level). From the 1900, and especially after the end of the Second World War, a progressive expansion of the town could be identified in the valley. Also Berat features a castle (locally known as the Kala) mainly built in the 13th century, which origins date back to the 4th century BC. The city was taken under Roman control in the II century B.C. During the middle ages, Berat was able to stay relatively unscathed due to the natural and human-built defenses. The city walls, which formed a triangular shape, were also built during this medieval period. In the XVth century, under Ottoman domination, Berat lived a period of urban and demo- graphic development, through the migration of the rural population and the creation of new districts. During the 18th century, Gjirokastra and Berat lived a prosperous period as demonstrated by the buildings with larger and better quality dwellings (which were required by the feudal class), and by the con- solidation of the urban and mobility structures (Pashako, 2015).

The fortress-houses were organized in 'neighborhood units', based on parental or 'clan' principles.

Gjirokastra has a low urban density, with irregular blocks, an articulated road hierarchy, and a large amount of green open spaces inside the blocks, among the buildings and in the spaces between the properties, with extensions of various shapes and densities. The ancient presence of small parks, orchards, gar- dens is still legible where now there are some uncultivated areas that cover the slope below the Castle. The urban configuration is comparable to an open hand, where the palm is the city core and the fingers are the city extensions. Between the 'fingers', gaps where watercourses run, some impassable on foot: vegetation areas free of construction, through which in the past paths crept up to the city core.

The urban structure mirrors a relatively horizontal society, with strong individualities competing with each other. The town, in fact, is not divided into zones according to hierarchical principles, and the main building organisms (the tower-houses) with their reference area are organized in blocks or neigh- bourhoods. The buildings were connected indirectly to the street through a gradual system of filters, made up of courtyards, gardens and private and semi-public spaces.

This horizontality of the social and urban structure in Gjirokastra returns a city that did not have urban squares as meeting grounds for the population, nor did it have a city hall for their representation. The only building embodying rule and administration was the castle, and the only social spaces were the religious complexes. The only public space of certain importance and structure is the crossroad of the bazaar, from where the residential areas were strictly separated.

Traditional cobblestone streets in Gjirokastra are paved with a mix of black shale and pink and white limestone. The problem of different slopes sometimes made stairways necessary. Berat houses have a more horizontal development and most of the time have a better connection to the outdoor spaces. Many houses are built in rows along the main streets, with predominantly horizontal layouts. These differences are partly explained by natural features: Berat has a smaller amount of rocky terrain, which builders sought to use as efficiently as possible by bunching houses together. Unlike Gjirokastra, which was ruled by major landowners often involved in reciprocal conflicts, the main occupations in Berat were trade and handicrafts, which are necessarily linked to a more open life and building style.

In Gjirokastra, three buildings have been identified as case studies. They are located in the Palorto district and they differ in their period of construction, state of conservation and current usage.The first case study is the Zeko family’s house, a building included in the national list of first-class monuments, actually used as a museum house. It started to be built in 1811, it underwent the first restoration from 1968 to 1975 (Riza, 2015), and a second one in 2004. The conservative restorations did not alter the planimetry and the construction systems. The house is located in a dominant position towards the south-western part of Gjirokastra. The two-wing planimetric scheme is composed of two rectangular blocks and a central connection element, with two large arches (kemer) on the facade, which sup- port the top floor terrace with a pergola (çardak), a privileged point of view towards the city and valley of the Drino.

The Fico House, built in 1902, represents a late development to the two-wing planimetric scheme and allows to understand the changes of the Gjirokastra dwelling, when they lost their defensive character. In the 20th century, the new buildings, while maintaining traditional planimetric and structural aspects, showed a stylistic evolution towards more western models. The house, which is easily identified because of its golden yellow facade, is included in the national list of first-class monuments.

The third building, the Dalipi House, whose construction dates back to the beginning of the 20th century, is currently in a state of abandonment with a process of increasing degradation, and continuous loss of wall portions. The reading of the morphological components and construction features allows to trace the history of the building, which has undergone numerous functional and technical transformations, and to understand some recurrent problems in the buildings of Gjirokastra.

The urban vernacular landscape of Gjirokastra is marked by the Ottoman detached tower-houses (kullë). The building served a living and defensive purposes, being at the same time a symbol of power and wealth. The interiors reflect the hospitable character of Gjirokastra people, as well as their propensity to display their status through opulent furnishings. The basic unit of the house is the residential room (oda), which maintains the same dimensions but presents different decorative elements in accordance with the people, family members or guests who used it.

Three variations of the kullë can be identified considering the planimetric and volume composition as the basic criterion for its classification: the perpendicular type, the one-wing type, and the two-wing type. The perpendicular variation, dating back to the late eighteenth century, is the simplest one: it consists of a prismatic block with a rectangular basis, with two or three storeys, linked by outer stairs. The one-wing variation, consisting of two blocks perpendicular to each other, is the most common kind of the Gjirokastra house. The two-wing variation, dating from the nineteenth century, has two parallelepiped blocks connected together by a central distribution volume.

The functional organization follows a vertical hierarchy. The ground floor, always built in stone, housed the service spaces: livestock (katoi), a space to store food reserves (qilari), big water cisterns to collect rainwater from the roof for the dry months of summer (stera), sometimes a mill and cereals (kube). The upper floors, more protected and safe, accommodated the living areas: the living room, called 'fire room' (oda e zjarrit), and the 'guest room', named 'good room' (oda e miqve or oda e mirë). The main rooms (oda) have low couches (sofa) and small ornate niches around three sides, while the fourth side is occupied by the musandra, a large cupboard, which stored mattresses and other bedding during the day. A short staircase concealed inside the musandra led to a small gallery (dhipato), where women and children used to retire during the meetings reserved to the men of the house and to the guests. Generally, the guest room is richly decorated, with floral paintings on the walls, ceilings, and on the fireplace, wardrobes with mouldings and notches.

The two residential floors usually have different uses depending on the seasons. The second floor, with small windows and thick stone walls, was used in winter (it is called dimerore, which means the wintry floor). The third and last floor (generally higher than the first), was used in summer (it is called beharore, which means Summer floor). It presents larger windows on the façades and thin walls with timber structure. The presence of the porch under the roof (cardak) provides climate benefits in winter, making the most sunny interior rooms; and also in summer, creating a more airy space, used for leisure, contemplation or for family festivities

In Berat there are two main types of dwellings, which can be divided into some subcategories or variants: the isolated unit (or house with çardak) and the aggregate one. The common compositional characters of both types consist of two levels building. The ground floor (basement) is in masonry. The upper floors may be in load-bearing masonry with the addition of light structures using timber walls. The large wooden roof is one of the most characteristic elements of the house, distinguished by the numerous folds and the large overhang of the eaves.

The isolated house gets its name from the central porch on the first floor called çardak, which held several functions, being at the same time a corridor, a living room during the hot months, or even the place for the treatment of agricultural products.

A variant of the isolated house, influenced by the land features, is the house with 'half floor'. In fact, the definition 'half floor' means a section jagged, with a greater extension of the surface of the first floor than the ground floor. The first floor has a greater surface area, both in the back of the house, thanks to the excavation of the soil, and in the front, with projecting wooden facades and typical bow windows, spread throughout the Ottoman cultural area, here called erkeri.

The aggregated type of dwelling has a lower extension than the one with the çardak. Its users are middle class people, employed in agriculture and handicrafts, without resources to own a house with çardak. This type has an aggregation scheme called 'string'. It has undergone transformations of the 19th century with the addition of erkeri. The houses have a functional scheme very similar to the house with çardak: the ground floor was used for storage (katoi), while the first floor was for family life. Here the rooms are fewer and smaller than the house with çardak

Building techniques used in Berat and Gjirokastra have been influenced both by the Albanian and the Ottoman tradition. The heavy stone construction of the lower floors has its roots in the rural Albanian tower house (kullë). The uppermost floors, with a timber structure (çatma), a wooden lath and plaster, a row of windows and terraces follow urban Ottoman building tradition.

Local stone is the main building material of the town: the walls, the roofs, the paving of the streets and the courtyards are made of blocks or slabs of local limestone and slate. Wood is used for the masonry reinforcement elements, the structures of the floors, the roofs and the uppermost walls.

Bearing walls, up to one meter thick at their base, are built with local limestone hewn blocks and bound with a mortar composed of lime and river sand. In general, the foundations, up to 130 cm thick, are dry-walled, in order to allow the drainage of groundwater and prevent capillary rise.

Horizontal timber ties, made of oak or chestnut wood, are embedded along load bearing masonry. These wooden elements, two or three according to the thickness of the wall, are placed every 80-120 cm on both sides of the wall, connected by transverse wooden pieces; at the corner, they are ensured by a diagonal tie element. The horizontal timber ties, generally squared, are often visible on the interior side of the wall, while in the external side of the wall they are protected by a stone course, in order to protect them from the rain. This system allows to connect the external faces of the masonry and create horizontal planes to lay the successive layers of stone blocks, ensuring the longitudinal and transversal stability, and improving the anti-seismic building performance.

The thickness of the walls decreases by 10-20 cm for each floor. In the oldest walls, dating back to the XVII and XIX centuries, there are not always wood elements of reinforcement, but the connection of the two faces of the wall was ensured by large stone blocks, which occupy all or almost all the thickness of the wall. Sometimes, masonries are covered with a first layer of earthen mortar, then a layer of lime and sand covering plaster.

The walls of the upper floors and the internal partitions are built using the technique called çatma. This traditional technique consists of a frame made by vertical posts and horizontal battens, on which wooden boards are nailed. The frame is filled with waste material and stones. The plaster is composed of a first

layer, 2 cm thick, of straw and earth, and a second 5 cm straightening coat of lime, sand and wool. The wood and lime plaster is laid on the first layer with a trowel, and then it is floated for three or four days. A coat of lime milk paint is applied on it. The facades of the most notable houses (Zekate is an example) present tall arches (kemer), which often support an open roofed space or terrace (kameriye).

Barrel vaults are used to cover mainly entrances and tanks, which are located at the ground floor. They

The floors consist of wooden joists – with a cross section of 8 ÷12 x 8 ÷12 cm – placed each 35÷50 cm and nailed at either end on the horizontal timber beams embedded in the walls. Planking consists of pine wooden boards – with a cross section of 2 x 20 cm – which are directly nailed to the joist. Pine wood is also used for the windows; chestnut or beech wood are used to make shutters and doors; stairs are generally made of beech, oak or walnut wood.

The grey limestone slab roofs are an essential characteristic of the Gjjirokastra’s urban landscape. The number of chimneys on the roof was a symbol of the wealth of the homeowner. The internal wooden false ceilings hide the structure of the roof, so it has been possible to observe only a portion of the roof of the Zekate house, partially rebuilt following the last restoration. The supporting structure of the roof is made of oak beams nailed together, which take on a rather complex hyper-static three-dimension- al configuration, where all elements cooperate to support the heavy stone covering of the roof. A system of ceiling joists, with a cross section of 14÷18x15÷20 cm, the principal rafters who support the ridge beam, are connected to the edge beams (taban) through riveted joints. Ridge beam and principal rafters are also supported by vertical posts (called baballëk), which rest on horizontal beams. The principal rafters can also be supported by radial timber elements working as struts, which converge in the horizontal edge beams resting on a central wall or placed at 90 degrees on the ceiling joists. The common rafters, placed at a narrow distance, have a cross section of 5÷12 x 5÷12 cm. Wooden boards are fixed on them, at a distance of 5-8 cm from consist of blocks of accurately dressed stone, walled with lime mortar. The vault is generally 35 cm thick, above construction debris and small stones are laid and leveled each other. The grey slate stone slabs of the roof are approximately 1.5 cm thick and are placed on the boards, without mortar or connections through metal hooks. The larger slabs are placed in the lower part of the roof, which is to be the most stable, while the smaller ones are arranged in the upper part so as not to overload the structure and to reduce the thrust towards the lower layers. The eaves of the roof protrude 50-60 cm; the rafters that bear them (called testek) are supported by timber elements connected to the wall, at the height of the lower floor. The slope of the roofs is between 25-30 %. Constant maintenance, especially before and after the storms and torrential rains of the winter, is needed to avoid the movement of the slabs and the infiltration of water.

The most relevant initiatives addressed to a sustainable conservation and development of the sites are those carried out by two local NGOs: Gjirokastra Conservation and Development Organization (GC- DO) and Cultural Heritage without Borders (CHwB). For more than ten years, both NGOs have been carrying out activities aiming to save the ruined heritage of the towns, and to rebuild interest and capacities, through actions of dissemination, training, restoration and active involvement of the inhabit. Regarding the dissemination of knowledge on cultural heritage, they produced books and brochures, aimed at promoting educational activities, which often involve kids. Since 2004, Gjirokastra Foundation has undertaken numerous restoration projects, with an approach focused on reuse and sustainability, integrating training, business development, and community outreach. These include the rehabilitation of: Zekate house (2004–2005), the bazaar (2007), the fountains and the square of a 17th century bathhouse (2004), and Babameto House (2010–2013).

The Gjirokastra Experiential Tours project is another interesting action aimed at the involvement of the local communities in the management of cultural heritage. The goal of this project is promoting the local and natural resources of the area, through their inclusion in tourist experiences based on local traditions such as cooking, dancing or singing.

In terms of training, since 2007, CHwB has implemented 38 Regional Restoration Camps, during which young people and students collaborate with local workers to restore parts of protected build- ings. The value of the Restoration camps as a powerful educational and vocational training-ground has been internationally endorsed by the recognition in 2014 of the European Union Prize Europa Nostra Award in the category of “Education, Training and Awareness-Raising”.

From 2015, CHBwB has launched the Window to Albania marketing campaign, promoting cultural and sustainable tourism – in contrast with the global mass coastal tourism – and the discovery of local traditional craft in the building construction field.

CHwB also conducted a Disaster Risk Management plan in Gjirokastra and Berat, determining a building’s level of risk based on structural integrity and occupancy, level of historical content, and priority category. In addition to CHwB’s work, UNESCO held a workshop in 2011, focused on natural disasters that Berat faces, such as flooding, fire, and earthquakes, and considering what risks they pose to both people and the historical sites. It went on to lay out guidelines on what can be done to respond to these risks, as well as how to best prevent them.