Models

Explore interactive 3D models

Built in a defensive position at the heart of the Caliphate of Cordoba, Cuenca is an unusually well-preserved medieval fortified city. Conquered by the Castilians in the 12th century, it became a royal town and archdiocese endowed with important buildings, such as Spain’s first Gothic cathedral, and the famous casas colgadas (hanging houses), suspended from sheer cliffs overlooking the Huécar river. Taking full advantage of its location, the city towers above the magnificent countryside.

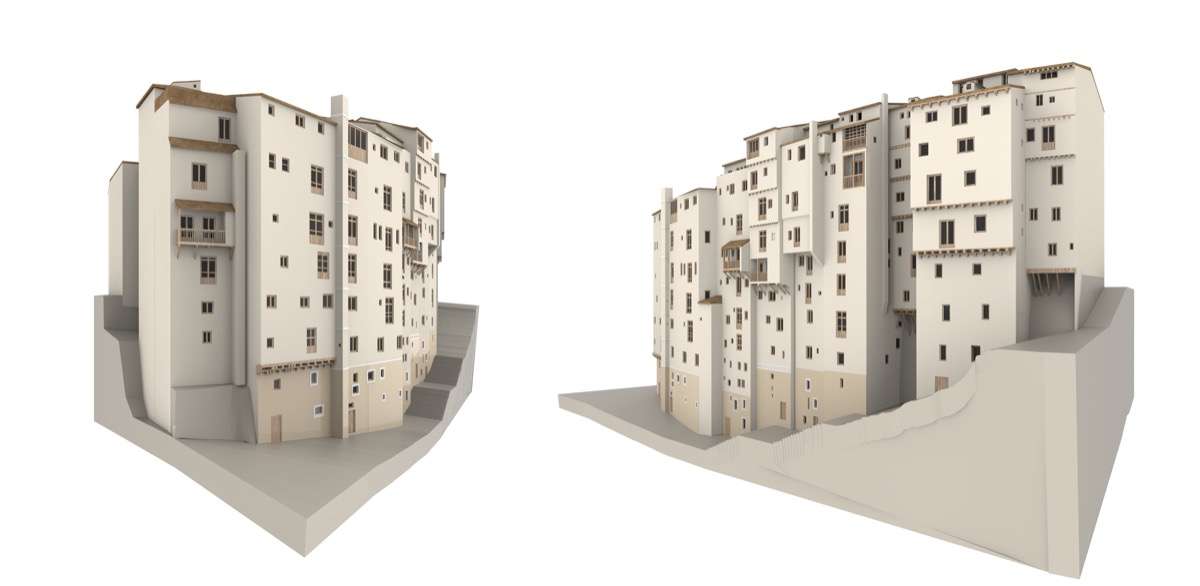

Cuenca 3D Model

Learn more about Cuenca, Spain

Built in a defensive position at the heart of the Caliphate of Cordoba, Cuenca is an unusually well-preserved medieval fortified city. Conquered by the Castilians in the 12th century, it became a royal town and bishopric endowed with important buildings, such as Spain's first Gothic cathedral, and the famous casas colgadas (hanging houses), suspended from sheer cliffs overlooking the Huécar river. Taking full advantage of its location, the city towers above the magnifificent countryside.

The large block of la Correría, now calle Alfonso VIII, still maintains many mediaeval architectural features. As a fortified city with little room for growth there was a need to build tall narrow buildings, known as skyscrapers. The foundations of some of the buildings on this street are at the foot of the cliffs, hidden behind the façade, while in an attempt to gain space inside the dwellings others are finished with balconies creating small overhangs on the cliff.

The organization of the façades of these two buildings differs greatly. The accessible façades of calle Alfonso VIII present a distribution characteristic of the 19th-century transformations which replaced mediaeval irregular layouts: the new façades are organized with regular openings, symmetrically distributed, decorated with mouldings or ironwork on the balconies, and careful renderings in characteristic shades of grey, yellow and purple (Muñoz Calero, 2017). In contrast, the back façades on calle Santa Catalina still maintain the irregular positioning of different-sized openings, the lack of decoration, and the frequent staggering of floors through overhangs (characteristic of mediaeval Cuenca) contrasting with the retrofitted façade on calle Alfonso VIII (Alau Massa et al., 1983).

The skyscrapers generally have long narrow floor plans, and are several storeys high above the level of the access street (generally three or four storeys) and descend at the back (sometimes up to eight floors) to find support at the foot of the cliff or braced by the system of overhanging balconies.

The constructive systems of these buildings are generally based on grid systems and lightweight assembled wood systems, with fillings of adobe, rubble, brick and even stone, forming “mixed” continuous structures (Muñoz Calero, 2017). Originally the interior distribution was articulated as a single unit, based on the prototype diagram of bourgeois mediaeval city: the ground floor was devoted to artisanal and commercial uses and the upper floors to the family residence, although the individual layout of these buildings determined a much more complex superimposition of functions, using the following levels as auxiliary spaces or quarters for rural use. However, after the remodelling in the second half of the 19th c. the subdivision of buildings was generally transformed creating a dwelling per storey, even on floors below ground.

The dwellings on calle San Juan are not as well-known as the façades overlooking the Júcar gorge and are more concealed from view. However, it should be stressed that they generally follow the same constructive guidelines as the buildings on the hills of the Huécar river, with the need to adapt to the natural steep terrain, although in this case the large rocks of the Júcar are still visible.

The hanging houses can be considered the most famous and representative civil buildings of Cuenca’s vernacular architecture. They are the most unique and special typology of traditional architecture in Cuenca. They have now been completely transformed, showing the passing of time, human intervention, and the idea of what this extraordinary group of buildings once was in the gorge of the Huécar river. These buildings date from the first half of the 15th c., with Ferrando de Madrid reported as the first known owner, followed by licenciado Gil Ramírez de Villaescusa, canon of Cuenca Cathedral. The outline of the block acquired a shape similar to the current one in 1469 (Ibáñez Martínez, 2016).

The four façades currently seen from the Huécar are not four independent dwellings, as Pedro Miguel Ibáñez Martínez states in his book ‘Las Casas Colgadas y el Museo de Arte Abstracto Español’ but three dwellings. The two façades on the right, looking from the river, are a single dwelling identified as the ‘Casa de la Bajada a San Pablo’ [‘House on the slope to San Pablo’]. The third of these façades, right next to the first two, is known as the ‘Casa del Centro’ [‘House in the centre’] and the one on the left is the ‘Casa de los escudos de Cañamares’ [‘House with the Cañamares coats of arms’], therefore referring by extension to the previous group of two, which has been a single dwelling since the late 18th century (Ibáñez Martínez, 2016). In the first third of the 20th century, the local residents and institutions tried to suggest new uses and a conservation and maintenance strategy for these homes, although occasional conflicts arose during this process. Up until this point the clifftop buildings on the Huécar gorge had been gradually disappearing, with a series of demolitions which began in the late 19th c. until only the 4 façades now visible were left. The “Urbanization plan for the city of Cuenca between the Júcar and Huécar rivers” presented in 1893 by Antonio Carlevaris proposed the almost entire destruction of the neighbourhoods of Santa María and San Martín, to be replaced by gardens, erasing the mediaeval spirit of this part of the city and its values as popular architecture (Muñoz Calero, 2017).

The present appearance and layout of these houses is the result of successive works of restoration and retrofitting. There is interesting graphic documentation of some of these interventions, such as that compiled by E. Torrallas in 1958, and published in the book by Ibáñez Martínez in 2016, edited by the University of Castilla-La Mancha and the Consorcio de la Ciudad de Cuenca. This publication also includes graphic information from 1962 compiled by Francisco León, municipal architect of Cuenca, who documented the original condition of the casa de la bajada and casa del centro, prior to current transformations. The casa de los escudos and casa del centro had been made into a single dwelling when the City Council acquired them, but it is un unclear when this happened or how it can be verified. Nor is there documented information on the interior before the casa del centro was completely emptied in 1963. However, there are some approximate plans on the interior layout prior to the project to adapt it to its new use as a Museum of Abstract Art in 1966, as the city council had ceded the building for use as a museum managed by the Fundación Juan March.

The most characteristic constructive elements of these façades in the Huécar gorge are the overhanging wood balconies. However, many of these elements are not original but rather are characteristic of the interventions mentioned above. The only constructive elements still conserved in their original condition are the small overhangs of the lower floor of the casa de los escudos.

The historic city centre of Cuenca is made up of the upper city or old city, the gorges of the Júcar and Huécar rivers, and the area outside the walls which marks the transition from the upper to the lower city. In this historic city centre it is worth highlighting the neighbourhood of San Martín, which extends along the limey crags formed by the Huécar river. The construction of traditional dwellings in this area adapts to the complex topography and is restructured into narrow elongated plots on solid rock foundations. This makes it possible to erect buildings of considerable height between party walls, veritable skyscrapers which give this hill its name (Muñoz Calero, 2017). The city’s vernacular architecture is characterized by the façades which lean on each other with intertwining layouts to ensure stability. The façade in the Huécar gorge is the best known, as it is the most accessible. In contrast, the urban occupation of the Júcar gorge is somewhat different, leaving the slope by the river exposed. The architecture hanging from the cliffs formed by these gorges is one of the city’s signs of identity.

In the area of the Júcar gorge, several actions were carried out to free up space and create gaps in the urban fabric for the purposes of renovation. However, it must be borne in mind that the current lookouts were once modest dwellings which filled these spaces, while dense vegetation from the river now covers the large stones found in the Júcar gorge (García Marchante, 2003). Although only four façades, now known as the Hanging Houses, survive in the Huécar gorge there were many more buildings built on the edge of the gorge and they formed one of the most incredible examples of the city’s vernacular architecture typology (Ibáñez Martínez, 2016).

The Upper City of Cuenca includes three areas with the most representative typologies of vernacular architecture in the city: the Hanging Houses in the Huécar gorge, the houses on calle de San Juan, overlooking the Júcar river (Figure 5), and the skyscrapers of la Correría, currently known as calle Alfonso VIII.

Two main dwelling typologies can be found in these areas. The first is built on rectangular plots with maximum façades measurements of 3.5 m, with several bays behind them and façades with only one or two openings per floor. In this type of dwelling, the ground floor was devoted to artisanal and manufacturing purposes, while the upper floors were residential. The most characteristic features of this typology include: “A single stretch of stair perpendicular to the façade, with no natural light, the sitting room window in the façade, the kitchen at the back and internal bedrooms with no ventilation or a small bedroom giving onto the sitting room” (Ibáñez Martínez, 2016). The second typology is that of the double module, sometimes original or the result of joining two single lots. The façade width in this typology is 4-7 m, which allows the inclusion of two to three openings per storey (Ibáñez Martínez, 2016).

Therefore, traditional architecture in Cuenca is characterized by deep dwellings built between party walls, with narrow façades. In these the ground floor is often built with masonry and the upper storeys use mixed framework systems with lightweight fillings, progressive overhanging floors, and openings following the mixed wooden structure (Ibáñez Martínez, 2016). In some exceptional cases the ground floor is also built using mixed systems of wooden framework. The skeleton structure makes it easy to include openings and allows space for open balconies and galleries. The ends of floor beams are often left exposed in these buildings, at times resting on a wall or course of the ground floor, while each floor overhangs (usually no more than 20 cm) over the previous one (Figure 6). The roof of this type of building is almost always a tiled gable roof, although a small number have hipped roofs and occasionally chamfers. The interior partitions in these dwellings are usually executed with framework elements and in some areas use wattle daubed with clay or gypsum (Flores López, 1973).