Video

Watch video content

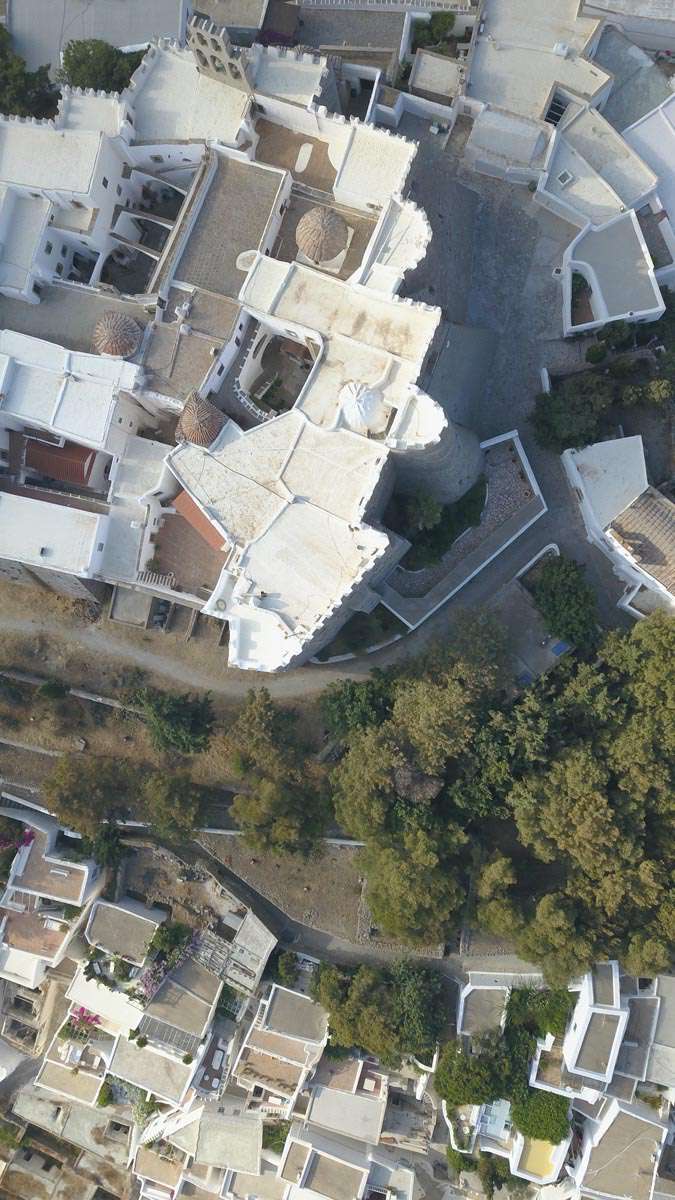

Patmos is one of the smallest and oldest inhabited islands of the Aegean Sea in the north of Dodecanese. It is known as one of the most important centers of Christian and Orthodox culture after St. John the Theologian wrote his gospel and the Apocalypse between 95-96 AD. The medieval city of Chorá is located in one of the highest points of the island and is characterized by a compact urban structure, with narrow streets and white plastered buildings that adapt to the morphology of the territory and develop around the imposing walls of the Monastery dedicated to St. John. The historic center (Chorá) with the Monastery of St. John the Theologian and the Cave of the Apocalypse was declared a World Heritage Site in 1999 for its high historical and architectural value which is still preserved today.

Watch video content

Learn more about Chorá, Greece

The Chora of Patmos, one of the best preserved and oldest of the Aegean Chora, is settled in one of the highest point of the island of Patmos, about 200 m above the sea. It is characterized by compact, whitewashed volumes, terraces that fit together and adapt to the morphology of the ground. Patmos is as one of the smallest inhabited islands the Dodecanese, a group of Greek islands in the Southeastern Aegean Sea, off the coast of Asia Minor. The island has an area 34.05 km2 and 3047 residents that are distributed between the settlements of Chora and Skala, the commercial port. The island is dominated by the Monastery of St. John the Divine (190m above sea level), located at the highest point of Chora, from which it is possible observing the morphology of the whole island, the neighboring islands and the coasts of Asia Minor. The island is long and narrow, with further narrowing in the middle; its morphology consists of a harmonious succession of rocky hills with scattered Mediterranean vegetation that end in an impressive variety of beaches and gulfs. The high landscape value of the Chora of Patmos is already recognized in the 1970-71 legislations as "historical and landscape monument" first, and subsequently as "historical monument and place of special beauty". Although new buildings have been identified on the borders, we can consider the boundaries of the settlement almost completely unchanged. Since 1999 The Historic Centre (Chorá) with the Monastery of Saint John the Theologian and the Cave of the Apocalypse on the Island of Patmos have been added to UNESCO's World Heritage List. The city represents one of the few settlements in Greece that has developed continuously since the 12th century.

According to the Greek mythology, Patmos was a sunken island that came into existence thanks to the divine intervention of the goddess and huntress of deer, Artemis, daughter of Leto. During the Hellenistic period (3rd century BC), the settlement of Patmos acquired the form of an acropolis, surrounded by a fortification wall and towers. Traces and remains of wall foundations from the 4th century B.C. were found in the area of present-day Skala. Since 95–96 AD the island entered the history of orthodoxy and of the Christian world when the apostle St. John the Divine spent his exile on the island and composed the Gospel and the Apocalypse. Nowadays it is one of the seven most important Christian world pilgrimage sites.

In 1088 the Bizantine Alexius Comnenus and the monk Christodoulos of Latros began to erect the Monastery dedicated to St. John, a task which took five years, with the help of 150 monks for the construction work, some experts from Constantinople for the planning of the Monastery, artisans from Trabzon for the fortification and unskilled labourers from the surrounding island. From 1132 an agrarian settlement began to develop around the base of the Monastery’s high walls. The local inhabitants were increased by immigrants that came from the surrounding islands and from the coast of Asia Minor across from Patmos to escape the persecution of the Turks. In 1453, after the dissolution of the Byzantine state a new wave of refugees from Constantinople settled in the Chora, building a new neighbourhood, called Alloteina. The new settlers, with a higher cultural level, introduced in Patmos new urban customs and ways of life, but they did not upset the existing economic and social structures that were controlled by the Monastery. The old and the new settlement were enclosed by a five-gated wall: this area was called Eso Kastro.

The conquest of the Venetian Rhodes by the Turks in 1522 led to a wide-scale reshuffling of the populations in the Dodecanese, including Patmos. In this period (1522–1636) several rural complexes arose outside the fortified zone (Eso Kastro), respecting the geomorphology of the site. Part of the settlements located near the monastery walls were demolished to make way for the crops needed for the subsistence of the monks.

The Venetian invasion of the island in 1659 did not cause structural changes of the settlement, but influenced the economic and social life that moved from the monastery to the community of Patmos. After the fall of Candax in 1669 many Cretan families sought refuge on the east part of the Chora. They founded the Kritika district and the first square of the settlement (the present square of Ayialevia) was created. In the following decades the population density increased, the urban tissue grew denser, the fortified walls were expanded and the rural complexes were integrated into the urban structure and fragmented into several housing units. On the steepest part of the hill overlooking Skala the district of Aporthiana developed. In the early decades of the 1800s Chora reached the economic and urban highest point. The period between 1832 and 1947, during the Italian occupation, was characterized by degrowth and migration. From 1947 to today, the development of the city resumes: this period is characterized by the appearance of mass tourism, the economic growth and the increase in construction activity.

The transition from the urbanized area of the Chora to the surrounding rural area are well defined. Chorá can be reached via the only driveway that runs along the entire island and a nineteenth-century pedestrian street that connects it with Skala. The fortified monastery dedicated to St. John the Theologian represents the volume that dominates the city. It is placed on the top of a promontory and has the appearance of a castle. The settlement features numerous small churches inserted in the urban fabric, some private chapels and others open to the community, which contain valuable pictorial elements. To the south-west of the town is the Zoodochos Pege female monastery, another large religious complex, founded in 1605.

The urban structure is compact and the streets are narrow and winding, with an irregular pattern without main axes, almost labyrinthine. The uneven alleys sometimes end in a dead end street leading to the houses The houses are arranged along the slope and, in general, are built on one or two floors, except for the 19th Neoclassical buildings, which can reach three-storey. These mansions stand out within the settlement for their dimensions. Most of them are located in Aporthiana, replacing the defensive wall towards the port of Skala.

The small courtyards and terraces, which occupy the part of the house facing the street, create a particular play of full and empty spaces. The presence of many covered passages, which were built after the expansion of the second floor of the houses, further characterizes the urban morphology.

In the 16th–17th centuries, agricultural complexes characterized by the desire for independence from the monastery and its social role spread in the area outside the first inhabited nucleus, underlined by the presence of a defensive wall and tools proper for various processes. The structure of the compound was characterized by several two-storey modules with alternate open and closed spaces. The ground floor included courtyards, cisterns, oven, kitchen, storages and grains, while on the upper floor were the sleeping area, the rooms and the terraces. Today these complexes have been incorporated into the urban sprawl and have been fragmented into several housing units.

The green urban areas are usually included in private properties and the few productive and commercial activities are distributed in the north-east side of the settlement. In ancient times there were two important internal axes; the commercial one which is the one still present today and the road with small artisan shops to the west. Windmills have been built since 1588 for grinding cereals and other agricultural products. Located in an area on the edge of the city, they are architectural elements that strongly mark its profile.

The first typology develops from the basic module (simple cell) in a multitude of variants that arise from the horizontal or vertical combination of one or more cells. It is the most widespread and characterizes the vernacular urban structure of Chorá.

It is formed between the 13th and 19th centuries. The variants depend on the way of aggregation of the simple cell and its position in the block that are influenced by the morphology of the site.

The main variations can be classified as:

The typology consists of houses with patio and a more or less complex aggregations of simple cells. The spatial changes of the single cell model different solutions analysed correspond to the needs and economic situations of families.

The evolutions of the two-storey patio-house consist of the horizontal extension through the repetition of adjoining cells, the insertion of irregular volumes or the connection of facing dwellings.

In this latter variant, the development takes place on the upper floor with a new room that fits over the street, thus creating the typical covered public passages. This link has a dual role: it was used as a guest room, but it also had a defensive function and was used as an overhead connection system to reach a protected area and defend themselves in case of attack.

The functional organization is always the same: with spaces for domestic use on the ground floor and representative spaces for guests and sleeping areas on the upper floor. More extensive and independent structures spread between the XVI and the XVII centuries as rural complexes, defined archondiko, and between the XVII and the XVIII centuries as urban complexes.

The first were born outside the city walls as agricultural residences/farms, independent from the social, economic and defensive role of the Monastery. These structures had their own walls, but with the urban spread were incorporated into the settlement of Chora. The second were born during the period of urbanization of Patmos as urban palaces of powerful shipowners and merchants, arranged inside the dense urban plot.

Two examples are Pagostas house, to the east, built about in 1606 near the female monastery of Zoodohos Pege, and Nikolaidis house-museum built between 1705 and 1796 and located northwest in the Kritika district. In general, these agglomerations consisted of several rooms arranged on two floors. They are characterized by alternating open and closed spaces, sheltered spaces and stairs. The ground floor included courtyards, cisterns, oven, kitchen and warehouses, on the upper floor were located the sleeping area, reception rooms and terraces. Many of these have their own private chapel.

Today, these agglomerations are generally fragmented between different owners and their original architectural form is changed in some cases.

The simplest and oldest form of dwelling consists of a single room on one floor, called monospito (mono+spiti) or ospition. The simplest nucleous has a rectangular volume 2,8 to 3,5 m x 7-8 m and 3,5 m high. The distance of the longitudinal walls depends on the length of the wooden beams; the ratio between the dimensions of a room is generally 1:2:1. Following the traditional way of measuring (xylometrima) used by experienced craftmesn before the metric unit, the length of a room correspond to 10 pieces of cane, the width and the height are 5 pieces. The buildings developed according to the morphology of the slope, parallel to the contour lines with the entrance mainly located on the short side. Internally the cell is divided in two areas. The first, next to the entrance, called spiti, is dedicated to the daily activities of the home such as cooking and handicrafts. The second, on the back of the building, called camari, was used for sleeping. The division between the two areas is obtained through a partition in stone, wood or cloth. The ratio between the sleeping and the living area is 1:2.

The first development of the basic cell saw the insertion of a new space between the street and the building: a little courtyard, called avlidaki, with an oven and underground cistern. In the case of larger courtyards it is possible to find a sink, a grinder, a fireplace or a rudimentary bathroom. The presence of the courtyard surrounded by high walls, in almost all the houses of Chora, shows the need of separation between the public and private space. For the lighting of the room there is a door and a window facing the avlidaki and no openings on the two longitudinal sides of monospito. Sometimes it is possible to find interior windows to light the rear.

The following extension of the house consist in the addition of a second floor or, where possible, in the horizontal repetition of the basic cells, which is arranged parallel or perpendicularly to form an ‘L’ with the existing building. Single-storey buildings are not very common today. In fact, most of the cases studied are relatively more articulated buildings and very often on two floors, the result of integration and transformation processes to meet space requirements. The two-storey house is called anogokatogo and consists in overlay of cells (anoi + katoi). The two-storey houses of Patmos differ from similar cases in mainland Greece, where the ground floor was generally used as a barn, warehouse or stable, since the ground floor here was part of the house.

The courtyard is divided into an entrance and an external area, covered by the upper terrace, and houses the oven and the cistern. The terrace, called pano avli, is reached by a main external staircase located near the entrance to the courtyard, and by an internal one, called katarrachias, which is located in the rear. The added terrace is supported by an arch, called kamariko, on the ground floor, which creates a communication between the yard and the remaining outdoor part. With the construction of the pano avli, the room on the ground floor became darker, so most of the daily tasks were generally conducted on the covered section of the avlidaki

On the first floor there is a formal space for special events, called sala or kalospito, usually 4,5 m wide and 7,5 m long, considered the most important place in the house and therefore much more refined in the furnishings. It was in fact the showcase of the house for visitors with paintings and photographs hanging on the walls, handicrafts of the occupants and pictures from travels to foreign lands. At the back of this room, adjoining the sala, there is the sleeping space: a wooden structure which was set up on the existing wooden floor. In the wealthiest residences this wooden structure is very articulated and heavily decorated with carved and painted decorations. This complex alcove takes the Greek name of ambataros. The best preserved example can be found in the Nikolaidis house-museum.

Subsequently another room was added to the upper floor, called ondas or nondas that had a dual role. It was used like an observation spot to control the street beneath and as a secret passageway connecting with the adjacent property which was on the other side of the street. In case of attack, the inhabitants had the opportunity to get into a protected area and defend themselves thanks to this system.

From 1832 three-storey buildings arose in the northern area of Chora, replacing the defensive wall towards the port of Skala. Maritime and commercial exchange with the outside favoured the spread on the island of new architectural styles, in particular of the neoclassical tradition. The different way of life and attitude of the inhabitants in addition to this new socio-economic developments change the architecture of the dwellings from the middle of the 19th century. The new buildings no longer followed the usual path in their composition and construction, compared to the traditional typology the volumes are compact and there is a lower flexibility of the internal spaces.

The date of the Italian occupation of the Dodecanese (1912) must be considered as the end of the vernacular architecture development in Patmos.

Stone is the predominant material on the rocky island and the main building material. The walls are made with two lithotypes: the granitic grey rock from the quarry of Manolakas, a tough, unwieldy and hard stone, and limestone rock (of a beige-ochre color) from the Megalos quarry which had less durability and hardness. In most cases the external walls have a limewash covering. The thickness of the masonry varies between 55 and 65 cm and, in general, decreases as the height of the building increases. Stones are squared and brought to hammer-dressed or straight cut finish before being laid. Stone elements can be more or less dressed, depending on the importance of the building. They have the approximate dimension of 20 x 20 x 40 cm and they are laid in horizontal courses of equal layers with uniform and staggered joints (Iakovides, Philippides, 1990).

Smaller stones, stone flakes or bricks are used to fill the uneven gaps remaining among the stones and to improve the uniformity of the wall texture. Larger blocks, which occupy the entire thickness of the wall, are used to connect the two external faces. The corner of the walls are made with particular attention, using ashlar blocks and very tight mortar joints. At the ground floor, corners are sliced off to facilitate the passage of loaded animal through the winding alleys of the Chorá. Corners and frames of the openings are not the plastered, unlike the rest of the building. The mortar used for the walls is always based on earth and lime, while the finishing plasters are composed of sand and lime, with the possible addition of straw. Terraces and fences are made with dry walls without the use of mortar.

The openings are generally few and located on the main front of the house. The height of a windows correspond to two canes of xylometrima, the sill of the windows is one cane. The structure is made using the technique of the architrave system, called mantomata. The stone lintel, with the dimensions of 30 x 30 x 150 cm, presents caved decoration, the date of construction, the name of the builder or symbols which protected the house against curses. Also the jambs could have glyphs and mouldings running around the contour of the frame. The elements of the mantomata (lintel and jambs) over the years have been reused in case of demolition of buildings, creating some confusion in the dating of buildings due to erroneous carved inscription. Few other openings present a round arch, always made with granite or limestone.

To span larger openings (from 3 to 3,5 m wide) for example for the support of the terrace or for the covering of public passage ways, arches or masonry vaults (locally called voltos or kamariko ) were used.

The facades sometimes have discontinuities owed to projections of the upper floor; these serve to give greater regularity to the first floor, as the ground floor often followed the uneven boundary lines.

The maximum span of the rooms of the buildings in Patmos is 3,5 m, which is why the most recurrent floor has simple warping. The wooden joists rests on the load bearing longitudinal walls. The warping of the joists is parallel to the shorter side of the cell that usually faces the street. Joists have regular-size, usually 7-12 x 8-15 cm, but sometimes rough trunks of 4-8 cm in diameter are used.

In case of bigger spans, for example in the covered passages, a main transversal structure, generally consisting of cypress wooden beams, is arranged every 50 to 120 cm. Above the joists wooden boards or reed branches were juxtaposed and constitute the support layer for the filling screed, composed of astivi (thick, tough, prickly bushes) and then a layer of ordinary sea-weed. Above a layer of earthen mortar is placed, and then the last finishing in ceramic tiles (keramìdia) or wooden boards. The entire floor structure reaches a thickness of maximum of 35 cm.

The traditionally most widespread roof of Patmos is flat, except for the churches, which usually have barrel-vaulted roofs. The structure of the roofs is quite similar to the floors but has a finishing layer that traditionally consists of earth, lime and crushed tiles (kourasani), which was well-tamped in order the necessary outflow so the rain water to would flow into the cistern (Philippides, 1990).

The stone paving is used in the entrance courtyard, wooden boards are arranged on the first floor and the typical Patmos ceramic tile is used to cover outdoor terraces and ground floor surfaces. Different compositions and decorations of the tiles enrich the interior floors.

The material fabric and design features of the significant elements and their organizational patterns have been well maintained and provide an authentic and credible expression of the site’s stylistic and typological models. All major monuments receive regular conservation attention but, despite the good general condition, there are numerous buildings within Chora in a state of decay or abandonment, mainly in the south-west area, the one most isolated from commercial activities. The bad condition of this area could be a consequence of the high costs to restoration and the depopulation, since when a space is lived spontaneous maintenance mechanisms take place.

The simplest form of dwelling consists of a rectangular base cell, supplemented by auxiliary spaces located mainly in the courtyard (patio), where the various domestic activities took place, such as cooking, handicrafts etc.

The base cell is called in Greek monospitum, a term that probably derives from the Byzantine hospitium. The length of the one-storey house is divided into three spaces, with the main entrance on the short side. The first space, called avli, is the entrance courtyard that usually has an oven, a sink and the opening of the underground cistern. The second space is called spiti and was the living and eating area, while the third, on the back of the room, is called camari and was the sleeping space.

Due to the originally dense structure of the town and the households growth, the one-storey house was integrated and transformed from time to time.

The two-storey house, in Greek anogokatogo, consists in the overlapping of two basic cells and it involved a different functional organization: on the ground floor were the entrance patio, the daily activities area and the storage; on the first floor were the entry terrace, the sala - that was the main reception room - and a sleeping area behind. The upper floor was connected to ground level by a main external staircase and a secondary wooden ladder on the rear side of the house. The patio was partially covered by the upper terrace; more specifically, the part where the oven and the opening of the cistern were.

The two-storey houses become the typical Patmian dwelling type and differ from similar Greek cases, in particular of the mainland Greece, where the ground floor was generally used as a barn, warehouse or stable, while in Patmos the ground floor was a living space.